by Chris

Kelly

I am often asked what

is required to become a game warden (aka: conservation officer). I have

given the same generic response for years. You must do well in high

school, earn a degree in conservation law enforcement, work a lot of

related seasonal jobs, volunteer time to the resource and be very, very

lucky. The other day, however, after giving that same response to some

young man, he replied, "No, what does it really take to be a game warden?"

I thought for a moment, and my reply went something like this:

A game warden must be

able to hike up shale slopes, slog through muskeg and field dress a

moose without wrinkling his uniform or getting his boots dirty. He must

survive a stormy day in a boat, arrest poachers that night, search for

evidence by moonlight, and still look sharp for court the next morning.

He must be in top physical condition to do these things despite surviving

on sunflower seeds and coffee.

He must be willing to

put his hands into the carcass of an elk that has been dead for days

in an effort to find the bullet that must still be in there - before

lunch. He will be able to trap and relocate a 750 pound bear the same

afternoon that he must arrest and relocate a 250 pound drunk - both

without incident.

He must work mornings,

nights, weekends and especially holidays while still trying to be a

husband and father (or wife and mother). He will miss birthdays, practices,

anniversaries and other important times simply to protect the resource.

He will do all of this and still feed a family of five on a meager civil

servant's paycheck.

He can look at a rancher's

dead Hereford calf and identify which of a dozen predators killed it

with nothing to go by but the feeding pattern on the carcass. He must

recite the biology, physiology, and migratory status of every vertebrate

with fins, fur or feathers that occupy his district. He knows all of

the local fish and game laws, but is also expected to react to any of

a thousand serious criminal offenses that can and do occur in remote

areas. He can describe the elements of a hundred different crime scenes.

He can recite the Charter of Rights, recent case law and a dozen relevant

Constitutional decisions - in his sleep. He can investigate, arrest,

search and detain a night hunter in less time than it takes six learned

judges to debate the legality of the stop.

He can deal with bear

maulings and crime scenes painted in hell, comfort the family of a drowning

victim, coax a confession from a wildlife trafficker, then help a child

remove a hook from the mouth of a fish.

He will spend countless

hours educating school and community groups on resource law and resource

protection. He will investigate and prosecute those who shoot moose

and then leave the carcass because it is "to much work" to salvage the

meat. Even when the investigation leads him to the only truck on a remote

road at 2:00 o'clock in the morning; even when four drunk individuals

fall out of that truck; he will gut, skin and quarter the moose before

giving it to the family in town that needs the meat. He will then return

home, and over breakfast, read in the paper how law enforcement isn't

sensitive to the rights of criminal suspects.

He must dispatch injured

and dying wildlife of every shape and size - even the cute ones. He

will care for orphaned and injured animals, though at times his house

may seem like a zoo. He must accept that he may have to dispatch the

very animals he is trying to help, usually after becoming attached to

them.

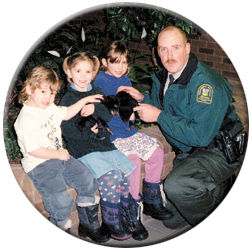

Officer

Chris Kelly, kids and cubs. Officer

Chris Kelly, kids and cubs.

He must be able to scan

every square inch of bush while walking into a kill site so that a bear

doesn't surprise him. He can't pass a road or cutline without turning

to see what is down it. He will always, always look out for his partner.

He must see the bulge in the jacket before he asks, "May I see what

you have there, Sir?" He will notice the vehicle tracks on that old,

dusty dead end road - then follow it because - you never know. He must

see and know the difference between a hunter and a poacher. He will

see that there are individuals who don't want him to notice these things.

He must know how to

survive in the bush alone. He must know how to get that old outboard

motor going again so that he doesn't have to survive in the bush alone.

He can put politics

out of his mind and find solace in the resource. He understands that

what is important to him may not be important to those above him. He

has a good sense of humor and can laugh at himself. He loves to argue.

He has made mistakes. He cares.

He realizes that there

is no such thing as a routine patrol. He knows that what goes around,

comes around. He is the guy you want beside you when all hell breaks

loose. He is the guy who wants to be there when all hell breaks loose.

He thinks of fallen comrades and old trails. Fellow game wardens are

family.

He believes in justice.

He believes in integrity. He believes in fair play. He leads by example.

He knows that the uniform does not make him a game warden. He doesn't

believe that "enforcement image" should be struck from the English language.

He does his job for pride, not money or recognition. He knows that if

the job is not properly done, there is no one to clean up after him.

The decisions he makes today will affect generations to come. He is

willing to commit his life to protect the natural resources that most

people enjoy and take for granted - even when he is standing all alone.

So you want to be a

Game Warden?

Chris Kelly is a member

of the Alberta Fish and Wildlife Officers Association in High Prairie.

|